Prolific niche publisher Mike Donaldson has spent decades photographing the biggest rock art collection on the planet. Ahead of the release of his new book, he reflects on the art’s deep significance.

For 20 years, Mike Donaldson has tracked down and eyeballed artworks unseen since Aboriginal people left the bush around a century ago. He has overcome everything from mad crocs to blistering conditions in some of the world's most remote places to capture images of paintings so ancient that they pre-date the last ice age.

Having published a handful of hefty coffee table tomes and shot more than 80,000 images of rock art and its landscape context in WA's Kimberley and Pilbara, Mike is keen to get this collection of paintings out there to a wider audience... before the elements take their toll and time runs out.

Many of the Kimberley art sites can only be accessed by backpacking for up to 100km through some of the roughest terrain in the state, an unpleasant prospect for most people. As a former exploration geologist, Mike facilitates the search for rock art, with the best preserved sites located in stable sandstone rock.

It would be easy to assume that this vast body of ancient artwork has survived for tens of thousands of years and should therefore last many more. But Mike says he has documented paintings that, in less than 30 years, have lost half their pigment due to flooding, for example.

.jpg)

Wandjinas are cloud spirits from the Dreamtime, believed to have made many of the Earth's topographic features, and to have been responsible for bringing animals, plants and people into existence.

He took the decision to self-publish his books of rock art in WA under the imprint Wildrocks Publications, to ensure full control over the design, size, format, and quality. He arrived at this conclusion after a fortuitous meeting about four years ago with book designer Trevor Vincent, who had been poised to retire from the Art Gallery of WA after 20 years.

To describe the publishing of his image collection as a labour of love would be to labour the point; Mike has sunk considerable personal funds into the books, along with many years of his life, in order to shine a meagre light on an otherwise little-known period of human history.

Aboriginal people have inhabited the continent for more than 50,000 years, and there are vast differences in the styles of art depicted across the Kimberley – from the delicately beautiful and intricate Gwion, or Bradshaw, images that experts estimate could be between 20,000 and 26,500 years old, to the colourful and impressive Wandjina images, believed to have been painted between 3000 and 4000 years ago.

An imposing man with a loping gait and a T-shirt that reads 'My Life is in Ruins', Mike jokes that his personal passion has turned into something of an obsession, beginning more than 30 years ago when he chanced upon a stunning piece of rock art while bushwalking.

"Many WA people know about French cave paintings," he says. "But many do not know that the Kimberley has the world's biggest rock art collection – nor what the art looks like."

He says part of the excitement of discovery is walking for weeks in country that has no sign of people – no footprints, no rubbish, no city sounds – and finding new art sites.

.jpg)

A family group of Ngunguru Gwions, or Tassel Bradshaws, floats across this sandstone rock face in the north Kimberley. These finely painted figures may be more than 20,000 years old.

It is the sort of country that only the occasional tenacious bushwalker – or helicopter – can get into. Particular areas of interest include the West Kimberley – especially the Drysdale River National Park, which has no access roads, and the Prince Regent National Park, which, until recently, was a nature reserve requiring government permission for access.

"This is the most pristine wild area in WA," says Mike. "There are no feral animals and, unlike everywhere else, no species loss. The only way in has been with a scientific research permit. It is as rugged as it gets."

But not so rugged that it wouldn't have made a sublime home for humans at different times.

"It is a lovely benign environment," Mike declares. "For much of the year, the weather is great, there is a huge amount of available food and water; plenty of wildlife, the rivers are teeming with fish, and there is abundant bush fruit.

"It would have been a kind of paradise." The Mitchell Plateau area is also rich in spectacular rock-art sites, but mostly in areas far away from the tourist drag. Thousands of sites there await re-discovery and documentation.

Ngunguru Gwions typically have long headresses and elaborate decorations, but never show facial detail or gender identification.

"Even the traditional Aboriginal owners, the Wunambal-Gambera people – recently granted Native Title over this area – have limited knowledge of these art sites," says Mike. But that is changing thanks to new programs designed to train Aboriginal people to find and record art sites.

For reasons largely unknown, archaeological records show that the region was unoccupied for periods of up to 5000 years at a time. Whether this was due to wars, climate change, famine or disease is unclear, says Mike.

"One possibility is that at the peak of the last ice age – about 20,000 years ago – the Kimberley was more arid, which may have pushed people to other areas."

Some of the earliest and most beautiful paintings in the region reflect fine paintwork, and have an almost African quality about them. But with no definitive means of dating them, they are a source of mystery... and some controversy.

These earlier paintings also include depictions of thylacines, which became extinct on the mainland about 4000 years ago.

.jpg)

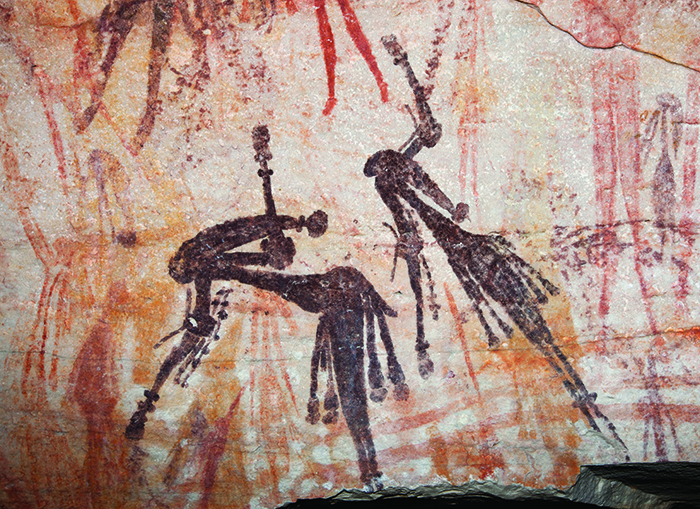

Mike with one of his books at a Gwion site on the Mitchell River, north Kimberley. These Yowna Gwions (Sash Bradshaws) are distinct from earlier Ngunuru Gwions in that they have a three-pronged 'sash' or skin bag instead of tassels, and unique 'tuft armbands'. They appear to be dancing, and hold multiple boomerangs.

It may seem counterintuitive to bring a glimpse of this world to the wider community, carrying as it does the risk of damage. But Mike says the art's remoteness keeps it safe – from humans at least.

"Governments have taken the view that these places are wilderness areas and never visited, and therefore don't need to be documented or protected," he says.

"I would like more people to see and appreciate these wonderful paintings, but that means more management of access. It is pretty sad

that many people are travelling to the Kimberley and 'doing' the Gibb River Road, Mitchell Plateau, and the Bungle Bungles, but they see little, if any, rock art.

"In other parts of Australia, great rock art sites have been opened to public access, with information supplied by traditional owners, and sometimes accessible only with Aboriginal guides.

"The sites at Kakadu in the Northern Territory are well managed and seen by thousands of visitors every year. The same at Carnarvon Gorge in Central Queensland, where elaborate timber walkways guide visitors to great art sites, but keep them at a safe distance from the paintings to avoid damage. Vandalism of art sites is always going to be a concern, but I think the best way to avoid it is to educate people about its cultural heritage and deep age," he says.

In the course of his work, Mike has won the cooperation of traditional owners, and forged constructive relationships, with royalties from his books contributing to local communities.

And the world is soon to learn much more about WA's rock art. Peak rock art body The Kimberley Foundation Australia has attracted eminent scholars to research issues such as dating techniques, paleoclimate studies, habitation history, artifact production, and food materials used over the last 40,000 years. The foundation is also behind the University of WA's Centre for Rock Art Research and Management – the largest rock art research organisation in the world.

If multiple tomes and decades of work were not enough, Mike is poised to produce yet another book, on the art of Pilbara's Depuch Island. Beyond that, he has two other books in the pipeline, including one covering the major art provinces of Australia. It's a dedication, he says, that befits the priceless heritage most of us know little about.