From high office in Canberra to the High Court of Australia, there is perhaps no more experienced political and legal hand in WA than Ian Viner. Here, he recalls duels in the corridors of power, his regret at lost progress in Indigenous affairs, and hopes for the legacy of the Fraser years.

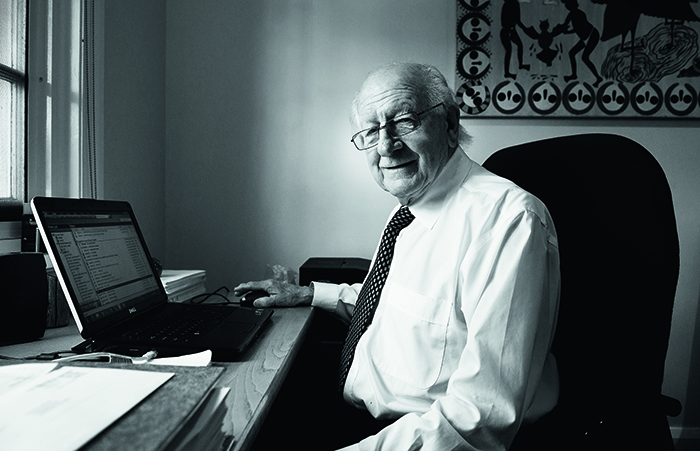

Upon entering a statesman's office, you will often confront the Wall of Important People – photographs of presidents and diplomats, and other such trophies accrued over the course of a distinguished life. But Queen's Counsel, former Commonwealth Minister and Order of Australia recipient Ian Viner has instead surrounded himself with Indigenous art, small gifts from grateful clients, and pictures of his 18 grandchildren. His remarkable career has taken him from high office in Canberra to the High Court of Australia and, at 82, he continues to criss-cross the country as a barrister and mediator, often working pro-bono for worthy causes.

"I try to keep weekends free for recreation," he chuckles, waving off what must be a common reaction of surprise at the extent of his workload. "And, of course, family is fundamental."

As Malcolm Fraser's Indigenous Affairs minister, he introduced laws under which the first freehold land titles were issued to Aboriginal people – his grassroots management of economic and social policy in the area is regarded today as an elusive gold standard among Indigenous leaders.

"It wasn't a ministry I expected," he says, recounting formative years spent in rural WA, during which Aboriginal people were often close by, but rarely seen. "But I embraced it. It was a life-changing personal and political experience."

In the past decade or so, his passion for his old portfolio has been reinvigorated by what he calls "retrograde events". In June 2007, he was delivering a paper on the fortieth anniversary of the referendum to include Aboriginal people under the Constitution. On the same evening, Prime Minister John Howard announced the highly divisive Northern Territory Intervention.

"I was appalled by it, by the political justification for it," he says of the move. "I wrote to Fraser and he was as appalled as I was. This was the first time in history that the Racial Discrimination Act had been suspended."

Influential Indigenous leaders, such as Noel Pearson and Marcia Langton, have criticised the "entrenched disinterest" of successive governments in ideas conceived beyond the Canberra bureaucracy. And, Ian says, decades of progress have indeed been lost in Indigenous affairs since Fraser left office.

"You had some grand statements from (Bob) Hawke, to the effect that he would make a treaty with Aboriginal people. But very much like Kevin Rudd with his apology, afterwards it was allowed to quietly disappear from the political agenda. There was deliberate policy under the Howard government to abolish the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, and the disgraceful view from Senator (Amanda) Vanstone as minister, that Aboriginal people were living in 'cultural museums'."

As for the self-declared Prime Minister for Indigenous Affairs, he says Tony Abbott "has got a long way to go". "All of the policy bureaucracy has moved into the Prime Minister's department, but the policies remain essentially the same," he says.

"Pearson has proposed 'empowered communities' as one solution, and in my discussions with Fraser it was thought that this might well be an answer. I don't pretend by any means that only we knew how to deal with Indigenous affairs. But governments need to show that they have confidence in Aboriginal people being able to manage their own affairs. Otherwise, they will always feel that they are living under the yoke of welfarism and bureaucracy."

Ian with Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser in 1980, during his time as Minister for Indigenous Affairs.

A cabinet minister when John Howard was treasurer, Ian frequently differed with his former colleague. But unlike Fraser, who famously dropped his membership of what had become – in his words – "no longer a Liberal Party, but a conservative party," Ian never lost faith in the movement. In the turbulent roles of Minister for Employment and Minister for Industrial Relations, he was variously depicted in cartoons as a boxer, cattle wrangler or dog handler in combat with the unions. He now speaks about his party with a sort of cautious hope, like a parent whose child has not quite met his or her potential.

"I don't accept the term 'conservative' for the Liberal Party," he says. "Other people may. But there was a deliberate attempt by Bob Hawke at the 1983 election, which largely succeeded, to paint an adverse

picture of the Liberals as regressive, out-of-date, or not forward-thinking. Even now, there is an attempt to portray Liberals as not interested in the working people of Australia, trying to invoke the old British divisions between the lower class and the nobility. Of which, of course, there is none in Australia.

"The values of the Liberal Party are fundamentally centrist – strong belief in private enterprise, rights and opportunity for the individual and smaller government."

A defining characteristic of Fraser's prime ministership was that the man himself enjoyed almost total loyalty throughout. Observing Tony Abbott's troubled first term, Ian recalls his own role in several leadership contests. He was one of four MPs who had cleared the way for Fraser by instigating the removal of Billy Snedden in 1974.

"As a group, we were persuaded that Snedden was no match for Whitlam and that we were going nowhere as an opposition. It might sound sanctimonious, but in those days it was the 'proper thing' to inform the deputy that the leader had lost your confidence."

Fraser got the leadership on his second try, but the spill against him was far more vicious. As a strong Fraser supporter and the minister who replaced the challenger, Andrew Peacock, in industrial relations, Ian became the target of an underhand campaign to personally discredit him.

Ian, with his wife, Ngaire.

"The spill in '81 was a very scarring experience," he says. "The difference was that, unlike Abbott, we had a challenger. When Fraser called for the vote, Peacock's forces were ready for us."

Since then, he notes a shift away from cabinet, or 'consensus style' government, in which the PM is only the first among equals.

"It is to be regretted that, over the past two decades, there has been an attempt to invoke presidential government. My own view, for what it's worth, is that the challenge to Abbott was a revolt against this way of conducting government." Ian says this was also the prevailing view of former ministers who discussed the matter with him after Fraser's funeral.

Throughout all his battles, Ian maintained a disciplined commitment to sport, playing hockey at an elite level. "Hockey was a huge outlet," he says. "While I was minister, we'd gotten into the grand final, and I had to take my togs to Canberra and practise on the lawn of Old Parliament House. There were a few occasions when I'd get off the plane on a Saturday, get dressed in the back of the Commonwealth car, and drive straight to the game." He would go on to captain the Australian masters international touring team in 1990.

After politics, Viner studied at Harvard Law School, became president of the Australian Bar Association, and appeared before the High Court, fighting to restrict government power over land, to uphold native title, and protect the rights of victims of negligence.

"Every time I think things are quietening down, I'll get a phone call from someone saying, 'Ian, we're under attack. Can you help us here?'" Most recently, he has gone in to bat for the Northern Land Council, defending traditional owners against the imposition of 100-year leases under the Forrest Review.

"I tell you, the Indigenous network around the country is not to be underestimated," he says.

Neither, evidently, is their unassuming champion, for whom it appears, there is still much work to be done.